Henryk Grossman

Henryk Grossman – alternative spelling: Henryk Grossmann (April 14, 1881, Kraków - November 24, 1950), was a Polish-German economist and historian of Jewish descent.

Born Kraków, Grossman studied economics and law in Kraków and Vienna. In 1925 he joined the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt. He left Germany in the 1930s and returned to become Professor of Political Economy at Leipzig University in 1949.

Grossman's key contribution to political-economic theory was his book, The Law of Accumulation and Breakdown of the Capitalist System, a study in Marxian crisis theory. It was published in Leipzig months before the Stock Market Crash of 1929.

Contents |

Early life and education

Grossman was born, as Chaskel Grossman, into a relatively prosperous Jewish family in Kraków, then a part of Austrian Galicia.[1] He joined the socialist movement around 1898, becoming a member of the Social Democratic Party of Galicia (GPSD), an affiliate of the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Austria.[2] The GPSD, led by Ignacy Daszyński, was formally Marxist, but dominated by Polish nationalists close to the Polish Socialist Party (PPS).[3] When the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party in Galicia (USPD) was formed in 1899, the GSPD became the Polish Social Democratic Party (PPSD) and the Polish nationalist current was strengthened.[4] Grossman led the resistance of orthodox Marxists to this current. Along with Karl Radek, he was active in the socialist student movement, particularly in Ruch (Movement), which included members of the PPSD as well as of the two socialist parties in the Kingdom of Poland, the PPS and the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL - led by Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches).[5] He was the main figure in the newspaper Zjednoczenie (Unification), which took a line close to the SDKPiL, against the pro-PPS politics of Ruchs main organ, Promień for which he was censured by the PPSD and its newspaper Naprzód.[6]

During this period, Grossman learned Yiddish and became involved in the Jewish workers movement in Kraków. Grossman was the founding secretary and theoretician of the Jewish Social Democratic Party of Galicia (JSDP) in 1905. The JSDP broke with the PPSD over the latter's belief that the Jewish workers should assimilate to Polish culture. It took a position close to the Bund, and was critical of the labour Zionism of the Poale Zion as well to assimilationist forms of socialism.[7] The JSDP sought to affiliate to the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Austria (the General Party), but this was refused. However, the JSDP was active alongside the General Party, for example for universal suffrage.

At the end of 1908, Grossman went to Vienna to study the Marxian economic historian Carl Grünberg, withdrawing from his leadership role in the JSDP (although he remained on its executive until 1911 and had contact with the small JSDP group in Vienna, the Ferdinand Lassalle Club).[8] With the destruction of the Austro-Hungarian empire at the end of World War I, Grossman became an economist in Poland, and joined the Communist Party of Poland.

Career

From 1922 to 1925, Grossman was Professor of economics at the Free University of Poland in Warsaw. He emigrated in 1925 to escape political persecution. He was invited to join the Marxian Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt by his former tutor Carl Grunberg.

Hitler's accession to power in 1933 forced him first to Paris, and then via Britain to New York, where he remained in relative isolation from 1937 until 1949. In that year he took up a professorship in political economy at the University of Leipzig in East Germany.

Grossman's Law of Accumulation and Breakdown of the Capitalist System was finally made available in English translation in 1979 by Jairus Banaji, for an Indian Trotskyist organisation, the Platform Tendency. A recent edition is: ISBN 0-7453-0459-1. However, it is a condensed version and lacks the important concluding chapter of the German original.

Contribution to Theory

While at Frankfurt in the mid-1920s, Grossman contended that a "general tendency to cling to the results" of Marx's theory in ignorance of the subtleties of "the method underlying Capital" was causing a catastrophic vulgarisation of Marxian thought - a trend which was undermining the revolutionary possibilities of the moment.

The Law of Accumulation was his attempt to demonstrate that marxian political economy had been underestimated by its critics - and by extension that revolutionary critiques of capitalism were still valid. Amongst other arguments, it sets forth the following demonstration (for a complete definition of the terms employed, the whole book is recommended):

The logical and mathematical basis of the law of breakdown

... Apart from the arithmetical and logical proofs that we have been given already, mathematicians may prefer the following more general form of presentation which avoids the purely arbitrary values of a concrete numerical example.

Meaning of the symbols

c = constant capital. Initial value = co. Value after j years = cj

v = variable capital. Initial value = vo. Value after j years = vj

s = rate of surplus value (written as a percentage of v)

ac = rate of accumulation of constant capital c

av = rate of accumulation of variable capital v

k = consumption share of capitalists

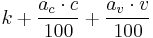

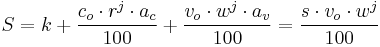

S = mass of surplus value, being:

Ω = organic composition of capital, or c:v

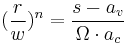

(Correction with respect to Grossman's text: From the formula below it follows that Grossman means by Ω the initial value of the organic composition of capital  :

: )

)

j = number of years

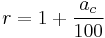

Further, let

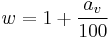

and let

The formula

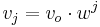

After j years, at the assumed rate of accumulation ac, the constant capital c reaches the level:

At the assumed rate of accumulation av, the variable capital v reaches the level:

The year after (j + 1) accumulation is continued as usual, according to the formula:

whence

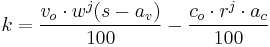

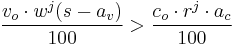

For k to be greater than 0, it is necessary that:

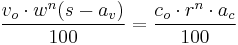

k = 0 for a year n, if:

(Note this line follows the German original in Das Akkumulations- und Zusammenbruchsgesetz des kapitalistischen Systems (zugleich eine Krisentheorie), because it is misspecified in the condensed English translation.)

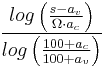

The timing of the absolute crisis is given by the point at which the consumption share of the entrepreneur vanishes completely, long after it has already started to decline. This means:

whence n =

This is a real number as long as s > av

But this is what we assume anyway throughout our investigation. Starting from time-point n, the mass of surplus value S is not sufficient to ensure the valorisation of c and v under the conditions postulated.

Discussion of the formula

The number of years n down to the absolute crisis thus depends on four conditions:

- The level of organic composition Ω. The higher this is the smaller the number of years. The crisis is accelerated.

- The rate of accumulation of the constant capital ac, which works in the same direction as the level of the organic composition of capital.

- The rate of accumulation of the variable capital av, which can work in either direction, sharpening the crisis or defusing it, and whose impact is therefore ambivalent.

- The level of the rate of surplus value s, which has a defusing impact; that is, the greater is s, the greater is the number of years n, so that the breakdown tendency is postponed.

The accumulation process could be continued if the earlier assumptions were modified:

- the rate of accumulation of the constant capital ac is reduced, and the tempo of accumulation slowed down;

- the constant capital is devalued which again reduces the rate of accumulation ac;

- labour power is devalued, hence wages cut, so that the rate of accumulation of variable capital av is reduced and the rate of surplus value s is enhanced;

- finally, capital is exported, so that again the rate of accumulation ac is reduced.

These four major cases allow us to deduce all the variations that are actually to be found in reality and which impart to the capitalist mode of production a certain elasticity ...

Much of the remainder of Grossman's book is devoted to exploring these "elasticities" or counter-crisis tendencies, tracking both their logical and their actual, historical development. Examples of each would include:

- Depressed interest rates, investment capital transferred to unproductive speculation, e.g. housing stock, art objects.

- Enlarged state sector bleeds value from the accumulation process via taxes. Wars destroy capital values.

- The Reserve army of labour (unemployed) created to discipline wage claims.

- Imperialism

Influence

Grossman's work has been of slight influence beyond the small fraction of the many Trotskyist political currents that have maintained awareness of it.

Paul Mattick's Economic Crisis and Crisis Theory published by Merlin Press in 1981 is an accessible introduction and discussion derived from Grossman's work.

References

- ^ Rick Kuhn Henryk Grossman and the Recovery of Marxism p.2

- ^ Rick Kuhn Henryk Grossman and the Recovery of Marxism p.4

- ^ Rick Kuhn Henryk Grossman and the Recovery of Marxism pp.4-7

- ^ Rick Kuhn Henryk Grossman and the Recovery of Marxism p.6

- ^ Rick Kuhn Henryk Grossman and the Recovery of Marxism pp.8-16

- ^ Rick Kuhn Henryk Grossman and the Recovery of Marxism pp.10-16

- ^ Rick Kuhn Henryk Grossman and the Recovery of Marxism pp.16-72

- ^ Rick Kuhn Henryk Grossman and the Recovery of Marxism pp.70-77

Further reading

- Grossman, Henryk The Law of Accumulation and Breakdown of the Capitalist System Pluto 1992 ISBN 0-7453-0459-1

- Kuhn, Rick Henryk Grossman and the Recovery of Marxism Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2007. ISBN 0-252-07352-5.

- Scheele, Juergen Zwischen Zusammenbruchsprognose und Positivismusverdikt. Studien zur politischen und intellektuellen Biographie Henryk Grossmanns (1881–1950) Frankfurt a.M., Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Wien: Peter Lang, 1999. ISBN 3-631-35153-4.

See also

- Reproduction (economics)

- Capital accumulation

- Crisis theory

- Tendency of the rate of profit to fall

- Surplus value

- Organic composition of capital

External links

- Grossman, Henryk, The Henryk Grossman Internet Archive. A collection of Grossman's writings.

- Harman, Chris, "Forgotten treasure: a new biography of Grossman", International Socialism, No. 114, Spring 2007. A review of Kuhn's Grossman biography.

- Heartfield, James, "Why Grossman still matters", Spiked Review of Books, No. 3, July 2007. Another review of Kuhn's Grossman biography.

- Kuhn, Rick, "Capital development", Socialist Review, No. 245, October 2000. A short biography of Henryk Grossman.

- Kuhn, Rick, "Economic crisis and socialist revolution: Henryk Grossman's Law of accumulation, its first critics and his responses", preprint version of an essay in Paul Zarembka and Susanne Soederberg (eds) Neoliberalism in crisis, accumulation and Rosa Luxemburg's Legacy: Research in Political Economy 21 Elsevier, Amsterdam 2004 pp. 181–22. A discussion of aspects of Grossman's contribution to the Marxist theory of economic crisis.

- Kuhn, Rick, "Henryk Grossman and the recovery of Marxism", preprint version of an article in Historical Materialism 13 (3), 2005. On Grossman's contributions to and place in the history of Marxism.

- Kuhn, Rick, "Henryk Grossman - Capitalist Expansion and Imperialism", International Socialist Review, No. 56, November 2007. Study on the relevance of Grossman's analysis for understanding globalisation and the current crisis.

- "On Henryk Grossman, A Revolutionary Marxist: An Interview with Rick Kuhn", Radical Notes, 9 April 2007